Much has been written about Jackie Jackson’s success as a Black female entrepreneur. Little is known, however, about her early struggles in life before her mercurial path to success. The Kilwins franchise owner opens up and shares previously undisclosed details with Chicago News Weekly about her childhood and young adult life.

A West Side Chicago native, Jackson was the youngest of seven siblings and lived in Rockwell Gardens, an East Garfield Park public housing project. Her parents, David Moore and Jessie Pearl Moore, divorced when she was six years old. With the four oldest siblings away in college, “My mother packed her bags … and moved to the south side of Chicago.”

They stayed with her late aunt, Helen Griffin. She lived in a 4B/2B, two-story brick house near the corner of 88th and Bishop: in the Brainerd neighborhood next door to the Beverly Hills community. “In that house, there had to be about ten to twelve children there. My aunt took in foster care children,” she shared. “It was fun, close-knit. It was like a clan because we all went to the same grammar school.”

After six months, they moved to 8955 S. Ada because her mother wanted a home just for her and her three young children. Jackson says her mother was a strong, independent woman who expected no handouts from her father: “So I grew up on the free lunch program.”

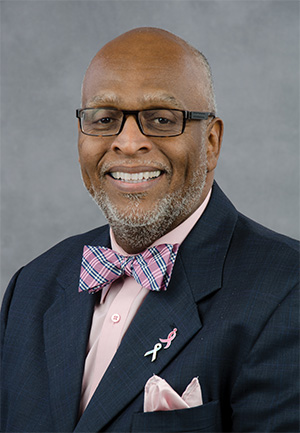

At Fort Dearborn Elementary School, Jackson had an encouraging 8th-grade teacher – now Dr. Willie Mack – who recognized her “leadership qualities.” “She had a great personality. She was awake,” he said in a phone interview.

courtesy of Dr. Mack

Jackson wanted to run for class president but “chickened out” after realizing she would be running against a more popular and prettier classmate. She recalls Mack pulling her to the side and saying, “Why don’t you want to run for class office? You don’t believe in yourself? I believe in you. I think if you ran, you could win.” “And that’s exactly what I did,” Jackson said. “I ran for this office, and I won.”

In front of her 8th-grade peers, Jackson gave a rhythmic speech written in part by her sisters that began: “I’m sure you heard of me before; yes, my name is Jackie Moore. President is what I’d like to be, and it’s up to you to vote for me. I don’t mean to bore you in any way, so listen up to what I have to say.” The entire class erupted into cheers, with kids standing on their desks and chairs shouting, “Yes! Yes!” Thanks to the encouragement and persistence of Dr. Mack, Jackson experienced a rush of confidence unlike anything else.

“I’m sure you heard of me before; yes, my name is Jackie Moore. President is what I’d like to be, and it’s up to you to vote for me. I don’t mean to bore you in any way, so listen up to what I have to say.”

Jackie Jackson’s eight grade speech

After graduation, Jackson couldn’t wait to get her first job. She applied for a work permit at thirteen and started working at Burger King. “At that time, there were no fast food restaurants anywhere near my neighborhood, so to eat a burger was like Christmas,” the entrepreneur declares. Jackson said she walked two miles back and forth to work, and surprisingly, the paycheck wasn’t her inspiration. “It was the free meals that always motivated me to come to work and give it my all. To this day, I still have nightmares of the cold baloney sandwiches on white bread with butter,” she says, referring to the meals given out through the free lunch program at school.

Several months later, a McDonald’s opened up blocks from Burger King. And Jackson wasted no time switching employers to work next to her friends from school. Then, one day, she greeted a customer: “Hi, welcome to McDonald’s,” she said gleefully. The customer turned out to be the franchise owner, John Bradshaw. He said to the manager Sam Harmon: “Who is this girl?” And he (Harmon) took me from behind the counter and said, ‘I want you to become a crew manager.” Jackson made her first promotion at fifteen, and Harmon gave her the money to go to Evergreen Plaza to buy a new work uniform: black slacks, a white shirt, and a fancy bow tie.

To prove herself in the new position, Jackson says: “I transitioned out of the polyester uniform … I learned everything from the grill to how to break down a shake machine. I was on top of the world with free meals every day and sitting in on management meetings. McDonald’s became my life and going to college was not in my plans.”

During the tell-all interview, Jackson shared with Chicago News Weekly that she worked hard throughout high school. But reality began to set in during her senior year at Chicago Vocational High School (CVS) as she watched all her friends apply to college. “I had no desire to go away to school,” she insisted, but “I started wanting to go to college once my boyfriend and all my friends were going, but I knew deep down I wasn’t college material.”

The entrepreneur admits her focus was not on school: “That wasn’t my route. I didn’t have the grades or the ambition to study. It just wasn’t me. I was really focused on working.” When asked what her mother had to say, Jackson pauses for a moment: “This is interesting; my mother somewhat became numb about it.” But Jackson insists, “She always gave me hope … She would tell me ‘You can have anything you want. You know how to get it. I believe in you.'”

Although Jackson had no desire to attend college, fate had a different plan. Around the spring of 1982, Jackson attended her best friend Arlicia Sanders Alston’s orientation at Western Michigan University (WMU). While Sanders Alston was inside the auditorium in the meeting, Jackson sat on a bench outside in the hallway. That’s when she ran into an administrator, who admonished her to join the others in the auditorium. “No, I’m not going here,” Jackson told him, “I’m waiting on a friend.”

“What college are you going to?” he asked. To which Jackson proudly quipped: “I’m not going to college; I’m going to work at McDonalds.” “Oh really,” he replied. “You don’t want to go to school?” “It’s a long story,” Jackson told the administrator. “I got a minute,” he responded. “What’s your story?”

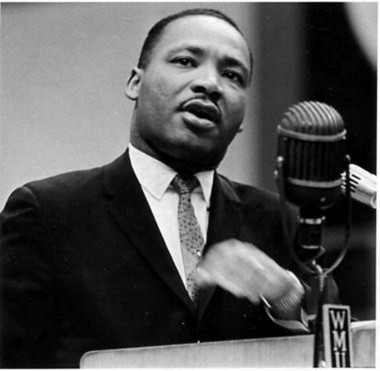

Jackson was talking to Danny Sledge, then-director of WMU’s Martin Luther King Jr. program. The unique program was created after King’s assassination in 1968 and geared towards “students who may have the potential to succeed, but who hadn’t demonstrated that potential in high school.”

In an e-mail to Chicago News Weekly, Sledge says: “The MLK Program provided an opportunity for [B]lack students who did not fully meet the university’s admission requirements…” Further, in a highly structured environment, the program “provided academic support and counseling, mentorship and development sessions to help them adjust to the expectations of the college environment and culture.”

Despite the chance encounter decades ago, Sledge vividly recalls that “she didn’t feel like she had the academic credentials to be admitted to college.” During the eighty-minute phone interview, Jackson shamelessly revealed that every college rejected her application. And one of the reasons was her ACT Composite score was a six. “I used to just strive to get a D because if I got a D, I didn’t have to go to summer school. I didn’t want nothing but a D, so I didn’t try to get anything better than a D.”

“I gave her information about the program and encouraged her to apply,” states Sledge “she looked like she was ready.” And at that moment, Jackson’s life was changed forever.

Unbeknownst to Jackson, her father, David Moore, had growing concerns about working at McDonald’s during her senior year. He knew his daughter’s future was at stake and struck a deal to pay her not to work. “How much are you making?” he asked. “I want you to quit your job and focus on school,” he told her. Therefore, she cut her hours to working weekends at McDonald’s to focus on school. “This is how I was able to bring my grades up,” she said.

Within three days of graduating from CVS, Jackson immersed herself in WMU’s MLK summer program. Jackson says she did very well, earning A’s and B’s with lots of support. She completed WMU in four years, earning a bachelor’s degree in Communications and Black American Studies.

Today, the uber-successful entrepreneur is the proud owner of five Kilwins in the Chicago metropolitan area and is planning a sixth location. Throughout the interview, Jackson stresses the importance of having many mentors in her life guiding her decisions. And she makes it clear that her faith in God and receiving the help she needed when she needed it made all the difference.

Sledge sums it up best: “Our youth today need our support … They need to see successful people who look just like them … who have stories just like Jackie’s … Many are diamonds in the rough. They just need to be polished and treated with care.”

This story first appeared in the Chicago News Weekly newspaper and has been edited and photos added.

Great story! I had no idea who owned Kilwins and I’m sooo pleasantly surprised! 😁

LikeLike